Following my diversions to the Niesen and the Schilthorn summits, I got back to my plans for walking Swiss trails in August. My planned third trail for 2024 was the Via Suvorov.

Before going on to talk about the trail itself, it is important to take a look at the background. Alexander Vasilyevich Suvorov was born in Moscow in 1729. He became a colonel in the Russian army during the Seven Years War of 1756 to 1763. In the 1790s, he was commanding a Russian army in Italy, sent there to support the Austrians. In 1798, Napoleon invaded Switzerland, and the combined cantons were unable to resist the invasion. As a result, Suvorov was ordered to march northwards in 1799, to go to Zürich, where he was to link up with another Russian army with the intention of forcing the French out of Switzerland. There were three potential routes for Suvorov to reach Zürich: the Great Saint Bernard Pass, the Gotthard Pass, or the San Berardino Pass. The most direct route was the Gotthard Pass, and Suvorov chose that one. By that time, Suvorov was nearly seventy years old, a Field-Marshall of the Russian Empire, and a veteran of sixty-three battles.

Suvorov and his army of 22,000 men left their quarters in Italy on 21st of September 1799, crossing into what is now Ticino canton of Switzerland, and heading for the Gotthard pass. It was then, and to a large extent still is, an axiom of military strategy that one should not fight uphill against an enemy, particularly in an area as steep as the approach to the pass. Suvorov disregarded this principle. The French, firing from behind rocks, harried Suvorov’s troops, but the Russians pushed forward and threw the French back, first to the pass itself and then beyond. With the pass secure, Suvorov was now fighting downhill and had the advantage. The French tried to make a stand at Hospental but were again pushed back. On the 25th of September, just 4 days after starting their march north, the Russians took the bridge at Andermatt. French resistance in the Reuss valley crumbled, and the Russians kept going.

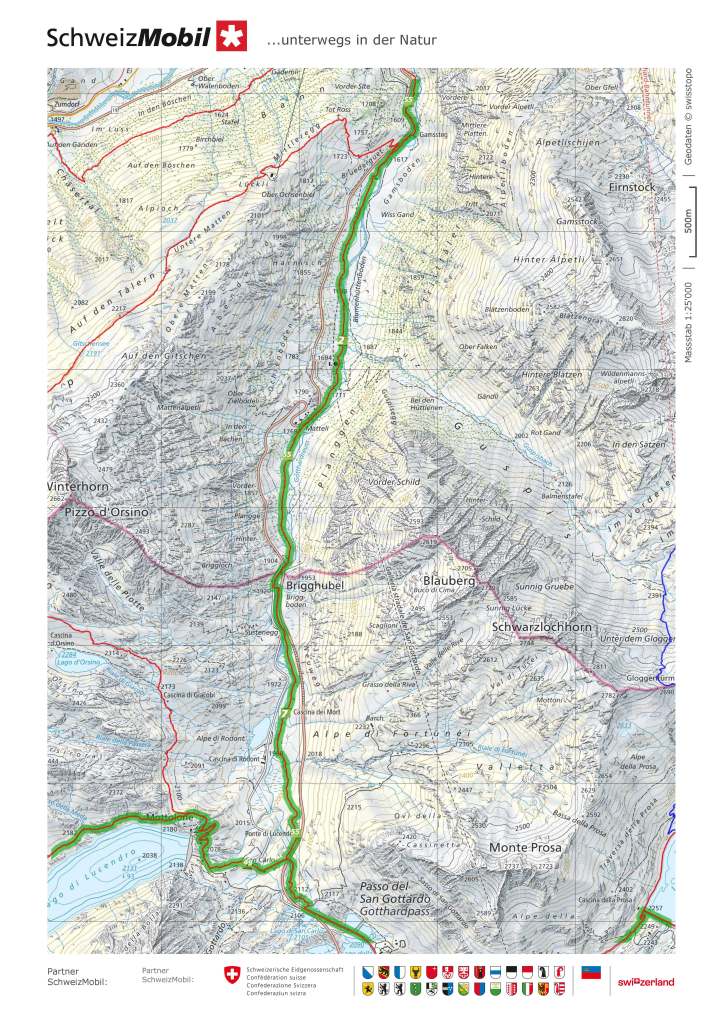

Suvorov’s march is commemorated in a trail that follows his route. The trail starts in Airolo and proceeds northwards to the pass. Today, the road to the Gotthard pass is popular with motorists, cyclists, and motorbikers. In Suvorov’s time, there was a kind of a road there, but today we would barely call it a trail, about three metres wide, and paved roughly with stone. Suvorov was supposed to have well over a thousand mules to carry supplies and provisions, but only just over seven hundred were delivered. The lack of supplies and provisions would dog the expedition later.

I started out from Airolo on a sunny morning and began the 900m ascent towards the pass. I was glad of the light breeze that cooled me down as I toiled my way upwards. The trail follows closely to the roadway, though there are places where it follows the old road, the rough stone surface still clear.

Just before arriving at the pass itself, there is a Capella dei Morti, a little stone church built in memory of the soldiers who died in the clashes between the Russians and the French. Suvorov lost about 1,200 men in reaching the pass. Just after the Capella, I came to the pass itself. There is what is referred to as the hospice at the pass, which dates from before Suvorov’s time. I suspect that it was more like an inn for travellers than what we would consider a hospice today. I chose to avail of one of the mobile food sellers catering for lots of car and motorbike tourists, and a few hikers.

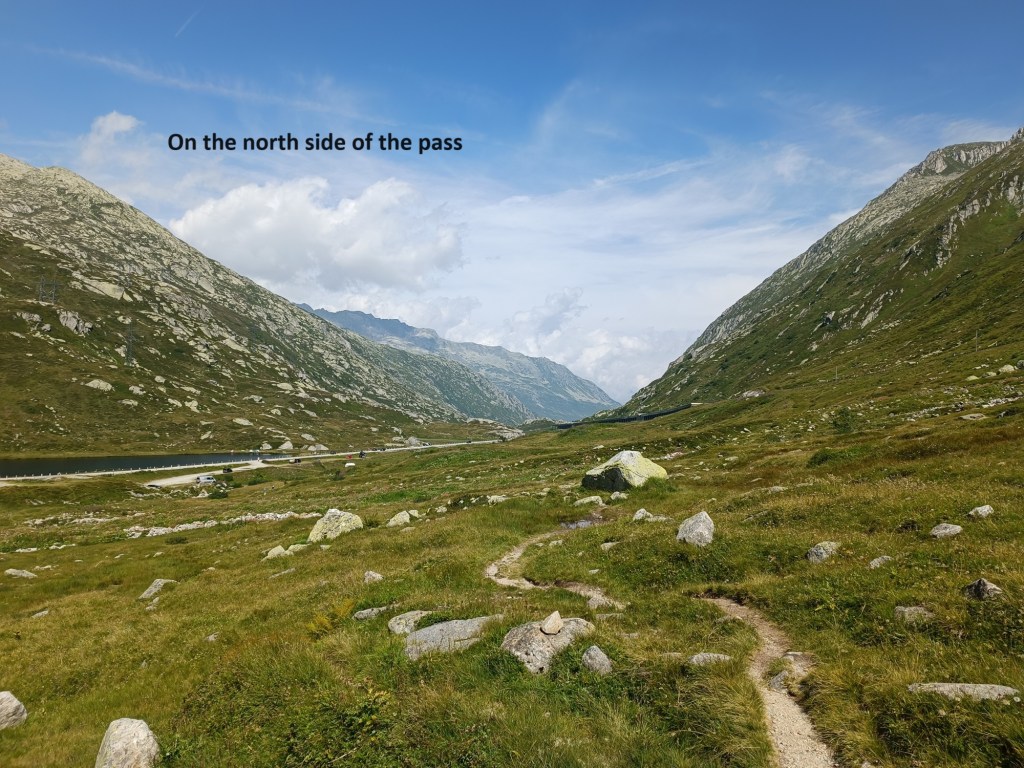

After taking a little time to enjoy a hot dog and a beer, I was on my way again. The northern side of the pass is gentler than the southern side. Once again, the old roadway is the basis for the trail in many places. It was reported to have taken carriages, but I can only surmise that it must have been a very rough ride indeed over what are basically large stone cobbles.

The trail went on down gradually over moorland until the farmlands until the village of Hospental came into view. Suvorov’s men had another fight with the French here, with the French troops withdrawing westwards towards the Furka Pass. Suvorov camped his army overnight, taking food from the local population, which the people could ill afford to give. Suvorov himself stayed overnight at the St. Gotthard inn, which is still standing and still in operation as a guesthouse today.

Like Suvorov, I continued on to Andermatt. In Andermatt, Suvorov once again forced the French out of the village, capturing valuable supplies in the process. I did not need supplies, though I was glad to stop for refreshments in the warm sunshine.

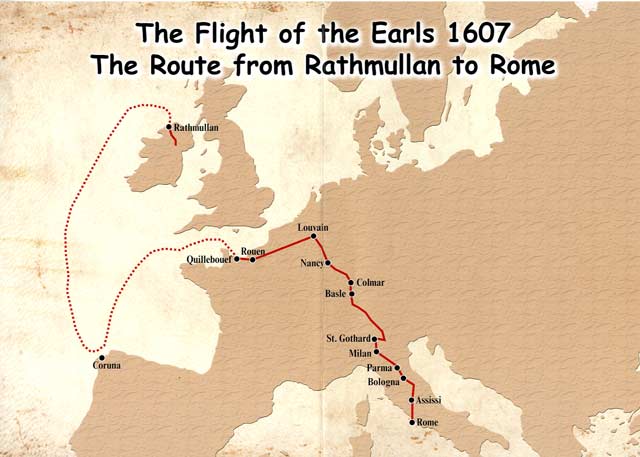

Leaving aside the exploits of Suvorov for a moment, Andermatt is also the site of a monument that is special to me. In the little church of the Altkirch area of the village is a monument to what in Ireland is referred to as The Flight of the Earls. In the late sixteenth century, the only major resistance to English domination over Ireland was coming from the Ulster Earls: O’Neill, O’Donnell, and Maguire. They had support from Spain. However, after defeat at the Battle of Kinsale in 1601, that resistance crumbled, and the earls signed the treaty of Mellifont in 1603. However, pressure on the Ulster Earls continued, to the point that in 1607, they decided to leave Ireland for Spain. They boarded a Spanish ship in the bay of Lough Swilly, and set sail, keeping well out to sea to avoid any English ships. However, weather forced them to divert to Quillebouef in France. France was at peace with England at the time and so was unwilling to accommodate the Irish, but allowed the earls to travel to Belgium, which was then under Spanish rule. The earls reached Louvain, only to find that Spain had also made peace with England, and they were not wanted there, though they were allowed to stay over the winter before moving on. The earls made their way south in 1608, through Colmar and Basel, and then going over the Gotthard pass to eventually reach Rome. It was a difficult journey. A chronicler of the journey recorded that O’Neill lost a horse carrying 120 pounds in money into a ravine. The departure of the Ulster Earls from Ireland marked the end of the old Gaelic system in Ireland. Very soon afterwards, English and Scottish settlers moved into Ulster, with effects that are still felt today.

The journey of the Irish earls is commemorated in that small monument at Altkirch.

As I went on, I came to a much bigger monument commemorating Suvorov’s march. The Russians do much bigger monuments than the Irish. The Suvorov monument was the site of a visit to Switzerland by the then Russian president, Dmitri Medvedev, in 2009. In recent years, with growth of Russophobia in Europe, it has been vandalised.

Just to the north of Andermatt, the Reuss goes through a deep and narrow ravine, tumbling in a cascade over rocks on its way. Today, there are road and rail bridges spanning the ravine, but for centuries, there was only one narrow stone bridge. It was built in the late sixteenth century and is referred to as The Devil’s Bridge. The legend is that when the bridge was proposed, the engineers advised that “only the devil could build a bridge in such a place”. The devil promptly appeared and offered to build the bridge, but on condition that the first soul to cross over would belong to him. The people of Andermatt accepted the offer, and when the devil built the bridge, they sent a billy goat across the bridge, thus tricking the devil. Today, the figure of a devil is mounted on the cliff face at the northern end of the road bridge.

The original bridge is still there, though it has been modified and rebuilt over the centuries. The trail uses that bridge to cross the ravine, and it is probably the one that Suvorov used. The French tried to stop the Russians from crossing the bridge, but Suvorov’s men pushed them back, with the French then retreating all the way down the valley. Suvorov followed. As well as the formal monument to Suvorov, the bar and restaurant beside the bridge also carry his name, a somewhat less formal recognition of the events of 1799. What Suvorov did not know was that on the same day that he was forcing the bridge at Andermatt, the other Russian army under General Korsakov was defeated near Zürich, and withdrew across the Rhein, leaving the French forces in control of that part of Switzerland. It was the first of two major setbacks for Suvorov, though one that he had no control over.

I continued on towards Göschenen. In the steep sided valley, the road, the railway, and the trail are all close together. It did not take long until I came to the Häderlisbrücke. This stone bridge was originally built in 1649. It was destroyed in a flood in 1987, and the current structure, a replica of the original, was built in 1991. That means that when the Irish Earls came this way in 1608, there was no bridge, but when Suvorov came down the valley in 1799, he almost certainly crossed that bridge.

After that, the valley widens out somewhat. By now, the sun had gone behind the mountains to the west, and when I reached Göschenen, the day was already cooling down and the light just starting to fade. I made my way to the station, where there were many other hikers also waiting for the train. After just a short wait, I boarded a train for the journey back to Basel.

My step count for the day was 43,619.